Background on Disinformation Trends

The objective of this analysis is to establish a framework to analyze, discover, and identify disinformation and influence campaigns that interfered with the public digital debates that took place in Colombia and Chile within the context of the series of episodes of social unrest that transpired in the last quarter of 2019.

We use the terminology information disorder as an umbrella term to cover the different terms that refer to disinformation and influence campaigns within the digital ecosystem. Terms such as echo chambers, misinformation, malinformation, hoaxes, or echo chambers, to name a few, are increasingly used within the context of information disorder, a phenomenon generally understood as a complex group of incentives for creating and disseminating digital messages, using different techniques aimed at achieving massive content distribution and amplification across multiple digital platforms. Within this context, it is important to clearly define key terms such as:

- Disinformation – Malevolent, fake, incorrect, or manipulative information with the deliberate aim or intention to confuse, sow discord or cause damage

- Misinformation – Incorrect information with no malintent from the original source. Information is shared but the damage caused is not intended

- Malinformation – Malevolent information shared with an intent to cause damage – as it is private information not produced to be shared in the public domain

- Computational Propaganda – Using algorithms, automated or human bots, and other techniques to massively and intentionally distribute misleading information through digital platforms

- Fake News – False news; either false or sensationalized information produced to intentionally appear as legitimate, real news

In late January a lengthy New York Times piece revealed recent US State Department findings that connected several Russian- and Venezuelan-linked profiles to abnormal activity in the public digital debates of some South American countries, including Chile, Colombia, and Bolivia. The signals of irregularities described in the New York Times article identified by the US State Department coincide with the tendencies and patterns uncovered by this analysis of the public digital sphere conversation in Chile and Colombia and with previous analyses of similar protests in other parts of the world such as the Yellow Vests Movement in France. Further, this analysis of abnormalities emerging in Chile and Colombia through a wide range of additional digital platforms and sources – including but not limited to YouTube, Facebook, public Telegram or public WhatsApp groups, or digital news media – demonstrates both the comprehensive and diverse nature of disinformation and, in particular, new strategies that have begun to surface amidst recent sociopolitical crises in South America that intend to connect digital influence with street violence and civil mobilization.

Of the countries assessed within our analysis, Chile was particularly vulnerable to the effects of disinformation campaigns and computational propaganda as exemplified both by Constella’s research and in recent research by the Oxford Internet Institute which highlighted Chile as one of the few countries globally which had not yet been subject to such influence campaigns. Oxford’s research shows that:

-

- 1. Organized social media manipulation campaigns have taken place in 70 countries (Colombia is identified as a country already subject to disinformation, but Chile is not), up sharply from 48 countries in 2018 and 28 countries in 2017.

-

- 2. Social media has become co-opted by many authoritarian regimes. In 26 countries, computational propaganda is being used as a tool of information control in three distinct ways: to suppress fundamental human rights, discredit political opponents, and drown out dissenting opinions.

-

- 3. A handful of sophisticated state actors use computational propaganda for foreign influence operations. Facebook and Twitter publicly attributed foreign influence operations to seven countries (China, India, Iran, Pakistan, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela) who have used these platforms to influence global audiences.

Based on substantial evidence from across the digital sphere, it can be concluded that these problematic phenomena affect a wide array of stakeholders across the entire digital ecosystem and as such are the responsibility of several key players in the digital sphere. This is not simply a problem limited to the major tech platforms and most frequently used social networks, as expanded upon in a piece that was recently published in collaboration with the Atlantic Council’s Disinfo Portal. It is critical to understand that disinformation activities operate atop vulnerabilities and a lack of trust exemplified by a growing skepticism of public institutions. For example, in Chile and Colombia, it is not that influence campaigns or disinformation created the unrest themselves. Rather, there were pre-existing conditions for social unrest – such as an erosion of institutional trust and economic inequality and insecurity, to name a few – that led to initial protests which then became a clear vulnerability for those countries and their citizens. Constella’s extensive research across the public digital sphere has provided insight into exactly how vulnerabilities are repeatedly exploited by disinformation campaigns in an environment where trust is devalued.

Executive Summary: Principal Conclusions – Comparative Analysis of the Sociopolitical Crises in Colombia and Chile

After conducting a detailed digital media analysis encompassing 101 million results from 7.6 million digital identities interacting in connection with the sociopolitical crises that transpired in Colombia and Chile in the last quarter of 2019, several common elements signaling potential phenomena related to information disorder were identified:

1. During the weeks following the emergence of the sociopolitical crises, Constella’s analysts identified a small number of accounts that generated a large volume of publications in relation to the unrest. In Colombia, 1% of users analyzed generated 33% of the analyzed results, and in Chile, 0.5% of users generated 28% of results. These high activity profiles flood the digital public debate with their comments and content and are considered statistically anomalous given the level of frequency of their activity over the period analyzed. This is a key indicator of information disorder parallel to previous conclusions derived from Constella’s research on polarization and abnormal activity in the digital sphere ahead of the 2019 European Union Parliamentary elections, where Constella’s analysts similarly identified a range of 0.05%-0.16% of total users in the conversation who were responsible for a range of 9.55%-11.1% of total activity across 5 countries in Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain) and were characterized by sustained and high-frequency diffusion of highly segmented messages and content. Colombia and Chile are particularly interesting as they share a common language, Spanish, and Constella’s analysis has identified a total of 175 anomalous identities that were actively participating in both crises. When researching the public geolocation indicated by these users or profiles, 58% of those publicly sharing their geolocation were geolocated in Venezuela.

2. Our algorithms identified significant influence from international media who have been habitually associated with foreign influence campaigns and the promotion of polarizing narratives that sow social discord. The elevated level of influence of international media is connected with the publication of similar news in both countries largely focused on evidence of the violence that occurred during the social crises with a special focus on the accusations towards public institutions and the public forces and security bodies.

a. The news outlet, Russia Today, also known as RT (2nd and 9th in the influence ranking and the 8th and 9th most shared media in Colombia and Chile, respectively), and TeleSur (77th and 26th in the influence ranking and the 14th and 15th most shared media in Colombia and Chile, respectively) stand out as highly relevant in this regard. Other international media with less relevance in the debate and not previously connected with foreign influence operations include BBC, DW, CNN, and The New York Times.

b. International journalists like Marco Teruggi – a correspondent in Venezuela for TeleSur who ranks among the Top 40 most influential authors in both countries and is also relevant in the digital debate in the sociopolitical crises of other countries, such as Bolivia and Ecuador – achieve high dissemination of their publications for what appears to be real-time, on-the-scene coverage directly from the demonstrations. Venezuelan politician and current member of the National Assembly of Venezuela, Diosdado Cabello’s program, “Con el Mazo Dando” is also present in both sociopolitical crises, ranking as the 22nd most shared media in Colombia and the 23rd in Chile.

3. Inna Afinogenova, from the RT channel Ahí Les Va, achieves high dissemination on videos in which she ironically comments on, the “real” causes that have provoked each of the sociopolitical crises. The video about Chile reaches 5.7 million views while the video of Colombia reaches 2.8 million. She also appears in videos about other countries that have experienced recent political and social turmoil, such as Bolivia, Venezuela, and Ecuador. Inna Afinogenova is a Russia Today (RT) journalist.

4. In both countries, media that present themselves as an alternative to traditional media, or “alternative media”, tend to be highly critical of the current government administrations and achieve relevance in the digital conversation.

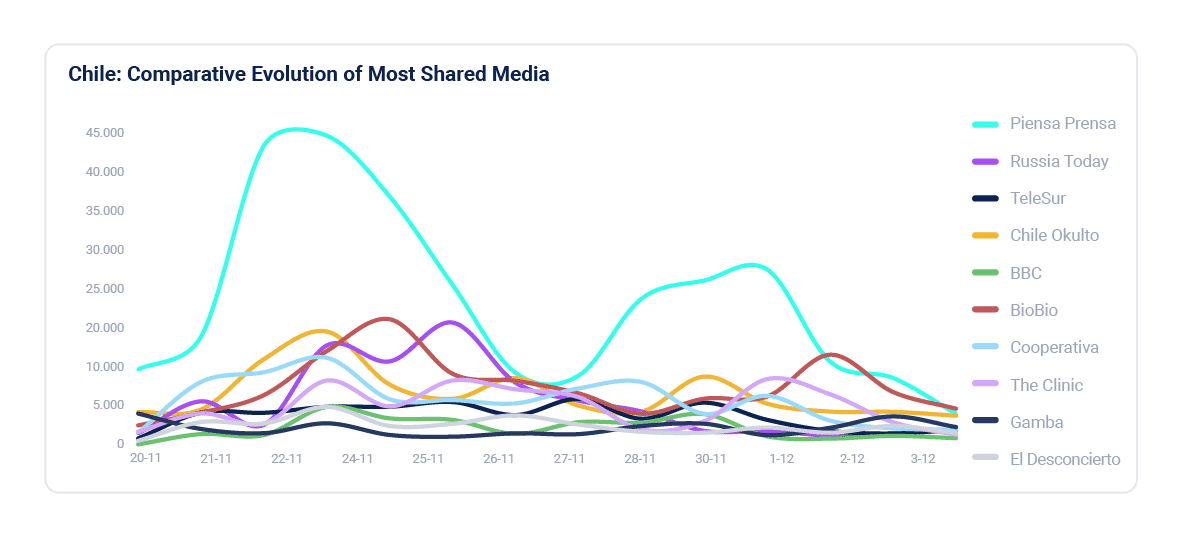

a. In Chile, blogs critical of the Government emerge and generate polarizing content while achieving substantial influence on social networks. Piensa Prensa and ChileOkulto are notable examples, placing as the 1st and 3rd profiles in the influence ranking. On Twitter alone, Piensa Prensa achieves almost four times as many retweets as the most relevant traditional media, attaining far superior engagement. These blogs which employ an extremely focused editorial strategy are among the most influential digital entities in the conversation, frequently posting graphic content recorded by collaborators or journalists at street-level, and they are the first to make the violence on the streets visible.

b. Alternative media, Colombia Informa, appears at 12th in the influence ranking. This media employs a communications strategy similar to Piensa Prensa or ChileOkulto as far as the audiovisual content shared on its social profiles without a link to the source. In this case, however, the names of the authors responsible for the content as well as the owners of the site are made public.

c. Other media presented as an alternative to traditional media are Las 2 Orillas (18th most shared media), and La Oreja Roja (30th) in Colombia and Gamba, (7th) El Desconcierto (10th), Ciper Chile (28th) and Interferencia (30th) in Chile. The users identified demonstrating abnormally high activity contribute substantially to the dissemination of these media, demonstrating a focus of their activity on the propagation of specific sites. 56.3% of shares achieved by Las 2 Orillas come from users demonstrating abnormally high activity. Likewise, 53.7% of times that La Oreja Roja is shared, it is shared by users classified as abnormal activity users. In Chile, users identified demonstrating abnormally high activity are responsible for 46.6% of Gamba’s shares and 50.5% of El Desconcierto’s shares.

5. As in other previously analyzed contexts of disinformation and polarization, the intensive use of public Telegram and WhatsApp groups as tools for the coordination and dissemination of images, news, and videos related to demonstrations and other events of interest is identified. What makes this analysis of special interest is that it identified that some of these public groups were also used to disseminate or encourage offline actions such as planting simulated bombs to disrupt the public and the obstruction of critical infrastructures such as airports or roads. This casts a certain degree of doubt on the effectiveness of Telegram’s recent announcements of a considerable effort to root out the abusers of the platform by both bolstering its technical capacity in countering malicious content and establishing close partnerships with international organizations. Additionally, multimedia content largely reflects the violence exercised by public law enforcement throughout the unrest. In Chile alone, 63 public Telegram groups (41% geolocated outside of Chile) and 61 public WhatsApp groups (18% geolocated outside of Chile) related to the demonstrations were identified. In Colombia, the volume is somewhat smaller, where Constella’s analysts detected 20 public Telegram groups (40% geolocated outside of Colombia) and 18 public WhatsApp groups, all from Colombia.

a. A group of public Telegram groups emerge in the public debate in both countries as well as in other Latin American countries, such as Bolivia. Some of these groups are established by foreign media such as Cuba Debate, EVTV Digital (in opposition to Nicolás Maduro), TeleSur TV and RT News. Other groups such as Topete GLZ and Geoestrategia1 (dedicated to the coverage of war conflicts), IslamOriente (with information on Islam) El Caporal or Official Group #PosLaVerdad, and a Bolivarian-Venezuelan group (Venezuela en Revolución) are also present in both Chile and Colombia. In Chile, there are several anarchist public Telegram groups with violent content that achieve a certain degree of relevance and public distribution.

6. Events on Facebook take center stage in mobilizing populations from different countries. 1 in 3 events related to the crises in both countries is identified by Facebook as having been organized abroad. Although it is not possible to clearly identify who the organizers of the events are, some foreign users have been identified as first to broadcast these events, especially those organized outside the country, on social networks. Highlights include TeleSur’s collaborator and producer in the United Kingdom, Pablo Navarrete (pablo_telesur). Navarrete is the first to share the events held in London in support of the demonstrations in Chile through his profile.

7. Beyond these elements which are common to both countries, certain differences between the two countries are identified with reference to the following:

Narratives: While in Chile the bulk of the conversation revolves around the criticisms directed at the Government and against a neoliberal economic model that exacerbates inequality and provokes social unrest, and conversations surrounding violent actions, in Colombia the focus of the conversation is on the violence, representing 54% of the total comments, compared to the 29% that such conversations represent in Chile.

Influential Media: In Chile, blogs like PiensaPrensa and ChileOkulto which are highly critical of the government and produce polarizing content are positioned towards the top of the influence ranking, being the first to make violence exercised by official security forces public. However, in Colombia, it is still the traditional media that leads much of the conversation.

Anti-mobilization Speeches: In Colombia, profiles that are extremely critical of the demonstrations emerge. Some of these profiles are positioned among the most influential in the public debate, such as @_El_Patriota or @elrepublicano09. These profiles encourage the population to take to the streets to defend shops, hold Gustavo Petro accountable for the deaths that occurred, and even criticize Dilan Cruz, the young man who was killed during the demonstrations. Among the identities detected with abnormally high activity, the anti-mobilization domain sincensura.co (shared 51% of the time by abnormal high activity users) is shared frequently. In Chile, although there are criticisms towards the demonstrators and the damage incurred during the unrest, the discourse is more focused on defending the Government’s economic and political management as well as their response to the crisis and openness for dialogue.

Dimensions and Evolution of the Public Digital Debate

Over a period of analysis ranging from October 18th, 2019 in Chile and November 20th, 2019 in Colombia to December 25th, 2019 in both countries, Constella’s team of data scientists analyzed the public digital sociopolitical debate in these two countries. Public data analyzed includes more than 88 million results coming from nearly 6 million digital identities in the sociopolitical crisis in Chile which has had an impact both nationally and internationally in terms of the sheer volume of results and also in terms of the duration of the conversation. The Paro Nacional in Colombia and the days after the early development of the unrest have a considerably smaller scope, reaching 13 million results from 1.6 million digital identities. While the conversation surrounding the crisis remains active in Chilean digital media today, in Colombia the conversation began to decline drastically during December. The unrest continued during the following days after the announcement of street demonstrations accompanied by slogans such as “Paro Nacional does not end here” and “Paro Nacional just begins” extending beyond the 21N. Over the last few weeks, the conversation in Colombia in relation to the unrest has been minimal.

19% of the geolocated conversation on the unrest in Chile originates outside of the country – specifically in Argentina (3.1%), Venezuela (2.7%), the United States (2.5%), and Spain (1.9%). Similarly, 19% of the geolocated conversation regarding the Paro Nacional in Colombia comes from foreign countries including Chile (4.9%), Venezuela (3.6%), the United States (2.3%), and Spain (1.9%). In the case of Chile, during the first week after the crisis had started, 30% of the comments could be geolocated as coming from outside of Chile, dropping to 14% in the third week of unrest. In Colombia, the conversation coming from outside of the country remains more stable, representing 22% during the first week and 17% in the following weeks.

It is important to note that both episodes of social unrest originate in response to the public’s discontent over the management of their current and past governments. There were pre-existing social and economic conditions including but not limited to lack of institutional trust or levels of inequality that plausibly served as a root cause for the initial unrest and discontentment which existed before influence campaigns started and the effects of information disorder manifested. In the case of Chile, following the announcement of the rise in the price of metro transportation fares, several demographics – but particularly the young population – begin to mobilize and organize a boycott of the subway, which then led to numerous demonstrations in different parts of the country and with the imposition of the Law of State Security by the Chilean government. In Colombia, a national strike was organized by those in opposition to President Iván Duque’s environmental, social, and economic policies, government’s management of the armed conflict with the FARC and other issues such as institutional corruption or the assassination of social and indigenous leaders, resulting in continued days of demonstrations in the country. Amidst the several social, political, and economic demands expressed by the demonstrators, these contentions are more evident in Chile, where the conversation revolves around the unrest related to the government of Sebastián Piñera, demanding his resignation as well as the resignation of other members of the Government, some of whom end up losing their position. It is important to note that these demands are also directed towards the neoliberal economic system that demonstrators hold largely responsible for the inequality that exists in the country, the privatization of basic services, and the high cost of living despite the low purchasing power of the population.

In Colombia, violence is the main axis of the conversation from November 21, comprising almost 54% of the conversation following the events suffered by Dilan Cruz, a young man who died after being shot during the demonstrations. From this moment the Colombian conversation focuses on the actions of ESMAD and the police, the episodes of vandalism, and the terrorist attack in Santander de Quilichao. In Chile, although there are also publications on the violence exercised by the Carabineros and the military, the proportion of the general conversation is much smaller and comes mostly from authors and media that are presented as an alternative to traditional media and are highly critical of the Chilean government.

Most Relevant Profiles in the Public Digital Sphere Debate in Chile and Colombia

Constella’s team conducted analyses on the most relevant users or digital identities in the general conversation in both Chile and Colombia for a period of 14 days after the emergence of the episodes of social unrest in both countries. For Chile, this means a period of analysis from October 18, 2019, to November 1st, 2019 and for Colombia, this means a period of analysis from November 20th,2019 to December 4th, 2019.

Among the 100 most relevant profiles in the two weeks after the emergence of the crises, 85% of these profiles are favorable to the demonstrations in Chile and 82% are favorable to those in Colombia. Among these profiles are opposition politicians such as Gustavo Petro in Colombia and Daniel Jadue in Chile, international media such as Russia Today and TeleSur, activists in support of the demonstrations such as Vagabundo Ilustrado (@vagoilustrado) in Chile and Mafe Carrascal (@MafeCarrascal) in Colombia, and journalists such as Marco Teruggi of TeleSur, present in the digital conversation in both Chile and Colombia. Additionally, in Chile, the most influential profiles are blogs that are highly critical of the government such as Piensa Prensa or ChileOkulto, and celebrities such as the artist, Mon Laferte, and the sportsman Claudio Bravo. The latter achieves high dissemination for his messages expressing concern about the situation and criticizing both inequality in the country and the management of the Government.

In both cases, as well as in other countries that have recently experienced unrest, international media hold substantial influence in the digital conversation. This is apparent in the case of media like Russia Today (RT), which becomes the second most influential profile in Colombia and the ninth in Chile, and the 8th and 9th most shared media respectively. Also prominent in both countries is the media outlet TeleSur, which is positioned as the 77th most influential profile in Colombia and the 26th in Chile, and the 14th and 15th most shared domain respectively. Moreover, TeleSur journalist Marco Teruggi, is among the 40 most influential profiles in both countries and is also present in the Bolivian demonstrations. These media play a key role in spreading content on violence and human rights violations, as well as in criticizing the economic systems and governments of both countries for their management in the face of the crisis.

The content above can be accessed at the following links:

1. twitter.com/ActualidadRT/status/1187228221336481793;

2. twitter.com/teleSURtv/status/1186831293281124352;

3. twitter.com/Marco_Teruggi/status/1198289749536133122;

4. www.facebook.com/watch/?v=416044425761447;

5. twitter.com/teleSURtv/status/1198377419905875970 ;

6. twitter.com/marco_teruggi/status/1197210546073985025?lang=en

These videos stand out for their high rates of dissemination. Among them is a video published by on the channel Ahí Les Va, a channel created by RT en Español in September 2019, starring the journalist Inna Afinogenova, in which she explains the “real” causes that are responsible for each of the episodes of social unrest in an ironic tone. The video about Chile reaches 5.7 million views while the video about Colombia achieves around 2.8 million. Like the previous media content, there are also videos assessing the situation of other countries that have experienced episodes of social unrest – such as Bolivia, Venezuela, and Ecuador – also starring Inna Afinogenova.

In both Colombia and Chile, high rates of dissemination are achieved by the “alternative media” that monitor demonstrations and unrest through a consistent focus on the violence exerted by security forces, playing a key role in the visibility of these incidents and events. This is especially noteworthy in Chile where two blogs with high influence on social networks emerge and are characterized through both a critical stance towards the government and the publishing of content with a graphic and polarizing nature. Piensa Prensa and ChileOkulto are positioned as the first and third profiles by influence ranking, and Piensa Prensa achieved almost four times as many retweets as the most relevant traditional media, Cooperativa and BioBio, although only on Twitter. The content these alternative sources offer is multimedia intensive and generally produced by collaborators and street-level reporters who record the content from mobile devices, focusing on explicitly violent content (shootings, stoppages, beatings, and lifeless or seriously injured people). The owners of these media are unknown, and they are not indicated on the website of the media itself nor in their social network profiles. Additionally, indications regarding how to access the ownership of the media, the editorial board, or publishing workers and collaborators are not readily visible. Ultimately, the articles and content are not signed by an author and it unclear how to access information regarding who oversees the domain.

The content above can be accessed at the following links:

1. twitter.com/PiensaPrensa/status/1186040150784122880

2. twitter.com/Chileokulto/status/1185165705022451713

3. twitter.com/Col_Informa/status/1198354100800380928

4. twitter.com/ManosLimpiasCo/status/1198244390856212481

In both Chile and Colombia, messages blaming the Government for encouraging violence through policing campaigns designed to generate panic are identified among the profiles supporting the demonstrations. Messages blaming both governments are also found among conservative profiles, including messages regarding alleged participation in the demonstrations and of looting by foreign “vandals”, allegedly mainly from Venezuela.

The content above can be accessed at the following links:

1. www.laorejaroja.com

2. www.las2orillas.co

3. www.gamba.cl

4. www.eldesconcierto.cl

5. www.elciudadano.com

6. interferencia.cl

Detection of Users Demonstrating Abnormal Activity

Constella’s data scientists conducted an analysis of digital identities demonstrating abnormally high activity and thus anomalous behavior in the public digital conversation in both Chile and Colombia for a period of 14 days after the emergence of the respective episodes of social unrest. For Chile, this means a period of analysis from October 18, 2019, to November 1st, 2019 and for Colombia, this means a period of analysis from November 20th to December 4th, 2019. In both sociopolitical crises, profiles with abnormally high activity are detected. In Colombia, 1% of accounts (8,521 identities) generate nearly 33% of posts (2,671,732), posting an average of 313.5 posts per author in the two weeks of analysis. In Chile, 0.5% of accounts (9,827 identities) generate almost 28% of the conversation (8,009,791 posts), publishing an average of 815.1 posts per author in the period of analysis.

Upon a more detailed examination of users demonstrating extremely frequent rates of activity, several anomalous identities with an exceptionally high level of activity stand out. 182 accounts in Colombia (0.02%) publish 256,070 posts (3%), with an average of 1,406 posts per author, and 217 authors in Chile (0.01%) publish 714,757 posts (2.5%), with an average of 3,293 posts per identity. Over the 14 days of analysis, the most active account in Colombia reaches a total of 4,113 posts while the most active account in Chile published a total of 6,798 posts. This implies more than 12 publications per hour for 14 days non-stop in the case of Colombia, and more than 20 per hour for 14 days non-stop in Chile.

In assessing the most statistically anomalous group of abnormal activity users based on their extreme frequency of posting, a total of 175 authors with abnormally high activity in both episodes of social unrest are identified. Of these authors, 58% of these accounts, who were publicly sharing their geolocation, are identified as coming from Venezuela.

Most Shared Domains in Relation to the Crises

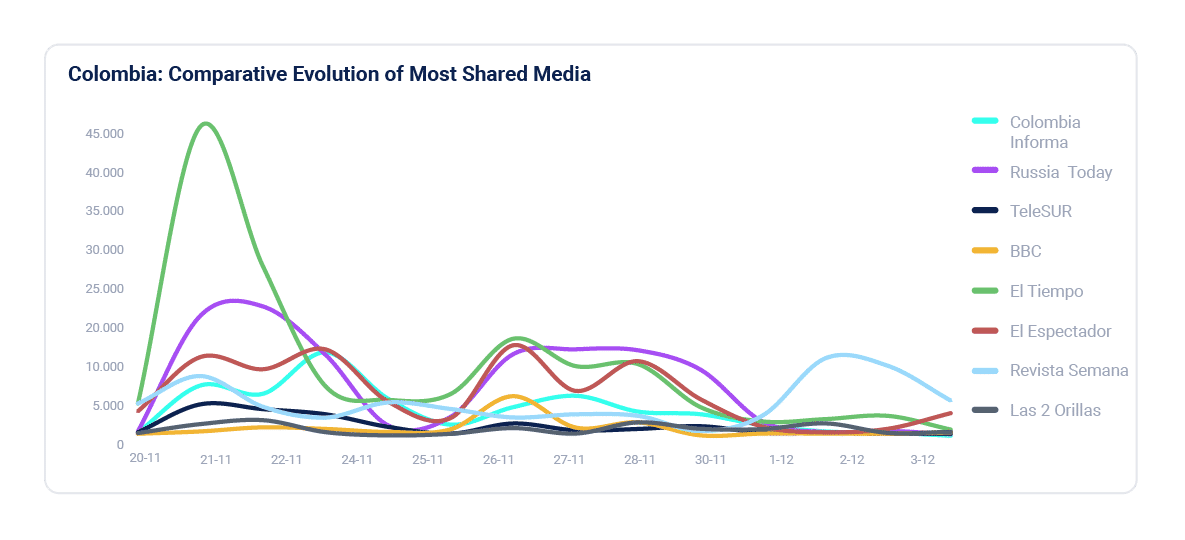

Traditional or mainstream media is the most shared type of media in both Chile and Colombia, although several alternative media are consistently shared with high frequency in the general digital conversation throughout the unrest. In Colombia, highlights of traditional media that were shared with high frequency include El Tiempo, El Espectador and Semana. Departing from the editorial position of the traditional media in Colombia, some sources are consistently critical of the Colombian government, such as La Oreja Roja, Las 2 Orillas and Canal 1. In addition to covering the spread of violence, these media achieve relevance for frequently sharing information on alleged acts undertaken by the government that purportedly aim to generate panic among the population in order to deter citizens from attending demonstrations. Furthermore, a majority of publications make reference to the violence responsible for the death of Dilan Cruz, an event that provoked a media response of considerable magnitude and served as a driver of the key narratives in Colombia. Also, it should be noted that Russia Today, described previously as employing a content strategy seen in other social crises around the world that involves a close-up, graphic, visual focus on the violence and unrest, is shared with high frequency throughout the debate.

As far as traditional media, BioBio and Cooperativa stand out among the most shared media in Chile during the crises. As in Colombia, the international media appear after the mainstream national media – the three most relevant in both cases being Russia Today, BBC and TeleSur, with Russia Today leading the pack. The most notable difference between the two countries is the content published by these sources. While in Colombia a majority of publications refer to the case of Dilan Cruz and the violence responsible for his death, in Chile the security and legislative measures that are undertaken by the Government and the initiatives presented in Parliament have a significant impact in the media.

Advanced Network Analysis of Most Shared Domains by Users in the Digital Conversation

To better understand how key media are shared and the role that abnormal activity users may play in interacting with these media in the public digital conversation in Colombia and Chile related to the periods of social unrest, COnstella’s data scientists conducted an advanced bi-modal network analysis of both domains and users. To achieve this, a bi-modal, non-directed network of Authors-Domains is created. The nodes can either represent Authors or Domains and the edges are constructed between the nodes when they interact, in this case, when an author shares a piece of content (URL based) that contains the Domain. Constella’s software ranks content influence similar to Google’s algorithms for web page ranking – the content from more relevant sites are likely to receive greater attention from more users over a sustained period of time. In order to enable the correct visualization of the graph the most shared Domains are used as a reference. Immediately below, a network including 191,210 users sharing 250 unique domains 712,912 times in the Colombian public digital conversation is visualized, with this bi-modal network enabling visualization of the concentration of users around domains, thus establishing the affinity between domains and users.

A total network of 391,479 users sharing 250 domains 1,096,165 times in the Chilean public digital conversation is visualized below.

To better understand the media that is most frequently shared by abnormal high activity users, Constella’s data scientists conducted a bi-modal network analysis of domains shared and abnormal high activity users identified participating in the public digital conversation. As mentioned previously, media like La Oreja Roja, Las 2 Orillas, and Canal 1 are consistently critical of the government and are among the most frequently shared domains by the 8,521 abnormal high activity authors. Las 2 Orillas and La Oreja Roja stand out in this regard, shared 56.3% and 53.7% of the time by abnormal high activity authors, respectively. Media critical of the demonstrations and unrest include sincensura.co. Of its total shares in the digital conversation, 51% of these shares were by abnormal high activity authors too. Another example is Extra Colombia, shared 97.2% of the time by abnormal high activity users and shared mainly on a page on which minute by minute coverage of the demonstrations was published.

Upon conducting a bi-modal network analysis of domains and abnormal activity users in the public digital conversation in Chile, several digital media sources emerge that define themselves as an alternative means of information to the traditional mainstream media. Frequently shared media among this group include Gamba, El Desconcierto, El Ciudadano, Ciper Chile, and Interferencia, among others. These digital news sources focus on attracting visibility to police brutality and to discrediting the Government and the administration that has overseen the crisis. As seen in Colombia, these alternative media in Chile achieve high dissemination, shared frequently by abnormal high activity users. Notably, El Desconcierto, Gamba, and Ciper Chile, of which 50.5%, 46.6% and 45.3% of their respective links have been shared by authors with abnormally high activity, fall into this category of alternative media shared at an elevated rate by a small, concentrated group of high activity users.

The Use of Public Telegram and WhatsApp Groups in Connection with the Crises

From the extended period of October 18th, 2019 in Chile and November 20th, 2019 in Colombia to December 25th, 2019 in both countries, Constella’s team analyzed the influence of public Telegram and WhatsApp groups to better understand the nature of the dissemination of content related to the social unrest in both countries. These are public groups, meaning they are created and made public in the public digital sphere with the intention of attracting other users to connect and share its content.

In both sociopolitical crises, the use of public Telegram and WhatsApp groups has been identified as a tool for both coordinating and disseminating multimedia content such as images, news, and videos that reflect the violence used by law enforcement related to the demonstrations and also for their selective use in the coordination of offline activities and demonstrations. In Chile alone, 63 public Telegram groups (41% geolocated outside Chile) and 61 public WhatsApp groups (18% geolocated outside Chile) related to the crises have been identified. In Colombia, the volume is somewhat smaller, with 20 public Telegram groups (40% geolocated outside Colombia) and 18 public WhatsApp groups related to the crises.

Several groups emerge in both Chile and Colombia as well as in other Latin American countries such as Bolivia. Among these groups, some are led by international media such as Cuba Debate, EVTV Digital (in opposition to Nicolás Maduro), TeleSur TV and RT news. Other groups such as Topete GLZ and Geostrategy1 (dedicated to the coverage of war conflicts), IslamOriente (offering information on Islam) El Caporal and Official Group #PosLaVerdad, and the Bolivarian-Venezuelan group, are also present in both episodes of social unrest. In addition to covering the different episodes of social unrest, some of these groups consistently share content seemingly intended for contemporary audiences. Content published over the period of analysis includes a mixture of posts related to key sociopolitical episodes varied with content related to pop culture themes such as sport, entertainment, and other topics of general interest that are commonly shared with frequency in the digital sphere.

During the unrest in Chile, public Telegram groups also appear with particularly explicit violent content such as the groups Archivando Chile, No Nos Callarán and Chile Despierta. Some of these groups publish and diffuse messages attempting organized or coordinated actions such as roadblocks or the distraction and subversion of the public security forces. By sharing anarchist content, Anarquismo (channel), AnArquismo (group) and Anarquismo en PDF stand out as relevant channels in the digital conversation. The first two are shared in other public Telegram groups with information about the Carabinieri private information hacking (Pacolog). The third, which has more than 2,500 members, contains a link to more than 800GB of downloadable anarchist content, including a video about Black Bloc content.

The Use of Facebook Groups to Support and Coordinate Demonstrations

From the extended period of October 18th, 2019 in Chile and November 20th, 2019 in Colombia to December 25th, 2019 in both countries, Constella’s team conducted research on the relevance of Facebook groups and the dissemination of content related to the social unrest. In both countries, the calls on Facebook for events related to demonstrations are relevant in the general conversation. Since October 18 in Chile, 135 Facebook events related to demonstrations against Piñera’s administration, the neoliberal system, or rallies for the citizen revolt are shared on social networks. In Colombia, 53 events were shared since November 20, mostly calling for street demonstrations and encouraging and assuring the population that the uprising is not over. Of the 135 events identified in connection with the unrest in Chile, 45 have been convened from outside of the country (33%), mainly from the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Spain.

A notable user account (@pablo_telesur), who identifies themselves as a collaborator/producer of TeleSur in the United Kingdom according to their profile, is the first to share Facebook events on his Twitter profile in support of the Chilean demonstrations from London. These include the BBC Peaceful Demonstration, which calls for “more dissemination of human rights abuses by the government of Sebastián Piñera”, Mass Protest for Chile in London – Saturday or Protest for Chile in London. He also shares the website alborada.net, which picks up an event called for October 21 in support of the Chilean people accompanied by the following message “Emergency Demo outside the Chilean Embassy this Monday. State of emergency in Chile: Enough is enough. Bring flags, banners, and ourselves! From 16:00 Chilean Embassy! London! St James Park!” This account also stands in solidarity with Colombia amidst the unrest and encourages collective support for the demonstrations.

In Colombia, of the 53 events, 18 have been organized from outside the country (34%), mostly in the United States, Canada and Argentina, and to a lesser degree in Chile, Spain, Germany, and New Zealand.

Among the organizers of the events, certain profiles of Colombian origin stand out, including Construyendo Comunidad, Somos Todos, Defendamos La PAZ Antioquia, Jaime es mi Gran Colombiano, and Informate UdeA, which has organized 21 events in support of demonstrations in Colombia, the last being called on the 7th of January (#ElParoContinua). Among the most successful events are the Paro Nacional of 21N, as well as those that encourage the continuation of the days of demonstrations such as Movilizacion Paro Nacional: Nos Unimos o nos hundimos, El PARO Continua: Cacerolazo Friday 5:00 pm Parque de las Deseos and Paro Nacional: Marcha Jueves 21 de Noviembre 5pm. The event in response to the death of Dilan Cruz, Estado Asesino is also successful. The user El Aguacate, a highly active and anti-bully Facebook profile that had already called for events against Uribe is also noteworthy.

Key Conclusions

1. Several anomalous identities, or abnormally high activity users, were identified participating in the debate. In Colombia, 1% of users analyzed generated 33% of the posts, and in Chile, 0.5% of users generated 28% of posts. These high activity profiles are considered statistically anomalous considering the level of frequency of their activity over the period analyzed. 58% of these abnormal high activity users who were publicly sharing their geolocation were located in Venezuela, indicating a significant percentage of abnormal high activity users participating in the public digital conversation in Colombia and Chile from outside of each country.

2. International media who have been habitually associated with foreign influence campaigns and the dissemination of polarizing narratives were relevant in the public digital conversations in both countries. International media such as RT and TeleSur achieved significant influence in the conversation while focusing on sharing graphic, violent content, in several cases through international correspondents and collaborators who offered on-the-scene, first-hand content of the events. These networks also place a focus on Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela within the context of social unrest.

3. In both countries, media presenting themselves as an alternative to traditional or mainstream media, or “alternative media”, tend to be highly critical of the current government administrations and achieve significant relevance in the digital conversation through their emphasis on graphic content related to the social unrest. Notable examples as described previously include, but are not limited to, Piensa Prensa, ChileOkulto, Presna Opal, Colombia Informa, Rival, Periódico Mapuche Werken, Radio Zapatista, Punto Final, Resumen Latinoamericano, and other media that offer an opposing narrative to the “mainstream media”. Other media presented as alternatives to mainstream media are Las 2 Orillas (18th most shared media) and La Oreja Roja (30th) in Colombia and Gamba (7th), El Desconcierto (10th), Ciper Chile (28th) and Interferencia (30th) in Chile. Accounts identified demonstrating abnormally high activity contribute substantially to the dissemination of these media. 56.3% of shares achieved by Las 2 Orillas come from users demonstrating abnormally high activity. Likewise, 53.7% of times that La Oreja Roja is shared, it is shared by users classified as abnormal activity users. In Chile, users identified demonstrating abnormally high activity are responsible for 46.6% of Gamba’s shares and 50.5% of El Desconcierto’s shares.

4. In Chile alone, 63 public Telegram groups (41% geolocated outside of Chile) and 61 public WhatsApp groups (18% geolocated outside of Chile) related to the demonstrations were identified. In Colombia, the volume is somewhat smaller, where Constella’s analysts detected 20 public Telegram groups (40% geolocated outside of Colombia) and 18 public WhatsApp groups, all from Colombia. As identified by Constella in other previously analyzed contexts of disinformation and polarization, the high-frequency use of public Telegram and WhatsApp groups serve as vehicles for the coordination and dissemination of images, news, and video content related to demonstrations as well as a key channel for the dissemination high volumes of content echoing the violence by public security forces. In this analysis, it is evident that some groups are being used for the coordination of offline activities, some of which could be considered violent and disruptive, thus casting a certain degree of doubt on the effectiveness of recent efforts from platforms to root out abusers and malicious content.

5. Public Telegram groups that appear in both countries as well as in other Latin American countries, such as Bolivia, are identified. Some of these groups are organized by international media like Cuba Debate, EVTV Digital (in opposition to Nicolás Maduro), TeleSur TV and RT News. Other groups such as Topete GLZ and Geoestrategia1 (dedicated to the coverage of war conflicts), IslamOriente (with information on Islam) El Caporal or Official Group #PosLaVerdad, and a Bolivarian-Venezuelan group (Venezuela en Revolución) are also present in both Chile and Colombia. In Chile, there are several anarchist public Telegram groups with violent content that achieve relevance. In addition to covering the different episodes of social unrest, some of the groups organized by international media (Cuba Debate, TeleSur, RT News) consistently share content seemingly intended for contemporary audiences in apparent efforts to achieve or maintain relevance, maximize reach, and attain increased engagement. Although our current analysis does not address this as a core hypothesis, an area of further research could include an evaluation of the effectiveness of different editorial strategies at increasing relevance and engagement. These varied content strategies could plausibly be effective at achieving a media strategy perceived as more neutral – despite a frequent focus on sociopolitical narratives – while broadening their core audiences beyond only users engaged with politics or with a similar ideological perspective, for example. In this way, certain types of narratives and content can be continuously introduced to a broader base of engaged users that might plausibly move the content from these public groups into private ones within the same platforms very easily.

6. Events on Facebook play a key role in mobilizing populations from different countries. 1 in 3 events related to the unrest in both countries is identified as being organized abroad. Although organizers of the events are not clearly identifiable, some foreign users have been noted as the first to broadcast these events, especially those organized outside the country, on social networks.

Through the detailed analysis, detection, and identification of several phenomena that can aid our understanding of the current state of information disorder in the public digital sphere, this in-depth research conducted by Constella’s team of analysts and data scientists demonstrates the various possibilities that exist and just a few of the numerous methods and means that are leveraged to impact the public digital conversation. As identified through this research (and as indicated in the concluding points above), significant influence and impact in the digital conversation can be seen in several forms including but not limited to the role of alternative and international media, abnormal activity users and anomalous identities, and alternative channels of message dissemination, as seen in Chile and Colombia with the presence and relevance of public Telegram and WhatsApp groups. As stated in other studies of this type, effective solution-building ultimately requires a multi-stakeholder approach in which technology platforms, media, academia, private and public organizations, and government work in a transparent and collaborative fashion to ensure the safety and integrity of the digital ecosystem.

Article written by Jonathan Nelson

Interested in our work? Please contact us at info@constellaintelligence.com. To learn more about Constella, subscribe to our newsletter below.